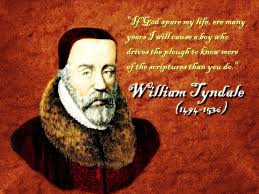

Faith Stories You Won’t Forget Series – William Tyndale

Introduction

William Tyndale was the first to translate the Bible into common English in the early 1500s. He did so against powerful and cruel opposition from the King of England and from sympathizers of the Roman Catholic church. Ultimately, Tyndale’s work cost him his life at the age of 42 when he was executed by strangulation on the stake and his dead body burned. Even so, his impact on the Protestant Reformation was substantial.

Indeed, according to Wikipedia:

“His dying request that the King of England’s eyes would be opened seemed to find its fulfillment just two years later with Henry’s authorization of The Great Bible for the Church of England—which was largely Tyndale’s own work. Hence, the Tyndale Bible, as it was known, continued to play a key role in spreading Reformation ideas across the English-speaking world and eventually, on the global British Empire. His version also worked prominently into the Geneva Bible which was taken to the New World to Jamestown in 1607, and on the Mayflower in 1620. Notably, in 1611, the 54 independent scholars who created the King James Version, drew significantly from Tyndale, as well as translations that descended from his. One estimate suggests the New Testament in the King James Version is 83% Tyndale’s, and the Old Testament 76%.”[7]

William Tyndale’s Life Story

The Life of William Tyndale

William Tyndale was born about 1494 in Gloucestershire. He took his B.A. at Oxford in 1512 and his M.A. in 1515. He also apparently spent time in Cambridge. He was for some time tutor to a Gloucestershire family. He disturbed the local divines by routing them at the dinner table with chapter and verse of scripture, and by translating Erasmus’ Enchiridion militis christiani (Handbook of the Christian Soldier, 1503). He was accused of heresy, but nothing was ever proved. John Foxe reports in his Acts and Monuments (1563) that one day at dinner, Tyndale announced to a visiting clergyman that he meant to translate the Bible so that ploughboys should be more educated than the clergyman himself.

He travelled to London to ask the Bishop, Cuthbert Tunstall, for support in his work. Tunstall rebuffed him. At this time, king Henry VIII was still the defender of the Catholic faith. Realising he could not translate the Bible in England, Tyndale accepted the help of a London merchant and went to Germany in 1524. He never returned to England, but lived a hand-to-mouth existence, dodging the Roman Catholic authorities. In 1525, he and his secretary moved to Cologne, Germany and began printing the New Testament. But Tyndale was betrayed, and fled up the Rhine to Worms. Here he started printing again, and the first complete printed New Testament in English appeared in February 1526. Copies began to arrive in England about a month later. In October, Tunstall had all the copies he could trace gathered and burned at St Paul’s Cross in London. Still they circulated. Tunstall arranged to buy them before they left the continent, so that they could be burned in bulk. Tyndale used the money this brought him for further translation and revision. At the same time, he wrote polemical treatises and expositions of the Bible. He began the Old Testament, apparently in Antwerp: Foxe tells how, sailing to Hamburg to print Deuteronomy, he was shipwrecked and lost everything, ‘both money, his copies, and time’, and started all over again, completing the Pentateuch between Easter and December. Back in Antwerp, Tyndale printed it in early January, 1530. Copies were in England by the summer. Revisions and shorter translations followed.

Tyndale’s writings were popular in England. Henry VIII, fearing Tyndale’s influence, sent an ambassador to persuade him to return to England. In a secret, nighttime meeting outside Antwerp city walls, Tyndale agreed that he would return to England, if the king would print an English Bible. By the time Henry published his Great Bible, Tyndale was already dead. In 1535, the fanatical Englishman Henry Phillips betrayed him to the Antwerp authorities and had him kidnapped. He was imprisoned at Vilvoorde, near Brussels, for sixteen months. A letter from him, in Latin, has survived, asking for a lamp, a blanket, and Hebrew texts, grammar and dictionary, so that he could study. Even Thomas Cromwell, the most powerful man next to King Henry VIII, moved to get him released: but Phillips in Belgium, acting for the papal authorities, blocked all the moves.

On the morning of 6 October 1536, now in the hands of the secular forces, he was taken to the place of execution, tied to the stake, strangled and burned. His last words reportedly were: “Oh Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.”

(adapted from David Daniell, Introduction, Tyndale’s New Testament [New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1989] viii-ix)

webpage contributed by Christina and Matthew DeCoursey

Etc.

So what do think? Quite a lot of influence against unrelenting opposition and all in a brief span of 42 years.

Comments/observations please!

Let’s talk about this hero of the faith.

Please use the Share Buttons for your friends on social media and/or send the blog link below directly to your friends.

Thanks!

I appreciate it.